Integral Ecology, AI, and Wage Futures of the Carolinas

There is always a choice

Turning Crisis into Conscious Choice

I write these words with a heart full of concern and hope. It is Juneteenth in the United States, and a time to reflect on all of our histories, achievements, and failures. Here’s a beautiful piece on the Juneteenth campouts happening in Mitchelville, SC (WaPo via archive), on Hilton Head.

Our region sits at a crossroads of change now, just as it did after the Civil War. The choices and intentions we make in the coming few years will direct our futures for decades to come as well. From intensifying heat waves and storms to the rise of automation and AI, it often feels like an uncertain future is rushing toward us.

Yet, amid these challenges, I sense an awakening, a growing realization that we can choose our path forward. This optimism is rooted in the concept of integral ecology, a way of seeing the world that weaves together environment, society, economy, and spirit into one whole. Rather than treating climate change, energy policy, job automation, and community well-being as separate issues, integral ecology calls us to recognize their profound interconnection. As a philosopher (and one of my Professors), Sean Kelly insists, “all human endeavor – from food production and resource use to economics, politics, and education – needs to be ecologized,” meaning considered in light of its impact on the entire Earth community. Conversely, ecology itself must draw on all fields of knowledge, including the wisdom of our spiritual traditions and local cultures such as Gullah Geechee, if we are to meet our moment.

“It is hot and promising to get hotter, so we’ll be very quick here”.

Gov. Henry McMaster, SC

Climate and Energy: Challenges in the Carolinas

The Carolinas are already feeling the strain of a changing climate and decades of energy decisions that prioritized short-term gains over long-term resilience. In North Carolina, for example, the state’s largest utility (Duke Energy) continues to pursue a controversial Carbon Plan that leans heavily on new natural gas plants. Climate activists warn that this fossil fuel buildout comes with a roadmap for increased carbon emissions that will “blow past a previously set 2030 deadline” for climate pollution reductions. One high-profile project, a massive pipeline expansion, would originate in eastern North Carolina and carry 1.6 billion cubic feet of natural gas per day to the Northeast. It’s sobering to think that even as scientists caution about “unabated sea-level rise, severe drought, and mass extinction” linked to fossil fuels, new pipelines and gas plants remain on the table. The impacts are not abstract: coastal Carolina communities face worsening flooding, inland areas endure record heat, and rural counties often host polluting infrastructure without seeing economic benefits. Some communities pay a much bigger price for this fossil fuel dependency. These are often low-income, Black, or indigenous towns, what environmental advocates call “environmental justice communities,” where residents have borne decades of pollution and neglect. A PCB landfill ignited America’s environmental justice movement in Warren County back in 1982, and their message is the same today: no community should be a sacrifice zone. Energy decisions must center on those most vulnerable.

South Carolina, too, is grappling with how to keep the lights on in an era of extreme heat without doubling down on climate-harming fuels. Under the blazing summer sun of June 2025, Governor Henry McMaster held a celebratory signing for a new law aimed at ensuring the state has plenty of power to meet its rapid growth. “It is hot and promising to get hotter,” McMaster quipped, alluding to a future of steamy Southern summers, “so we’ll be very quick here”. The law, passed with bipartisan support, is touted as a way to keep air conditioners humming and businesses thriving.

In practical terms, it clears the way for a 2,000-megawatt natural gas plant to be built jointly by Dominion Energy and Santee Cooper at a former coal site. It also streamlines regulations, letting utilities appeal permit denials directly to the state Supreme Court to avoid lengthy delays. On the surface, this is billed as proactive governance, “future-proofing” South Carolina’s grid for the 1.5 million new residents who have arrived in the 21st century to our beautiful state (welcome, if you’re new here!).

But scratch a little deeper, and worries emerge. Some legislators and community advocates questioned whether the law was written more to please industry than to protect citizens. Notably, no limits were set on energy-hungry data centers, meaning big tech companies could gobble up the new electricity supply, potentially raising costs for everyday Carolinians while offering few local jobs in return.

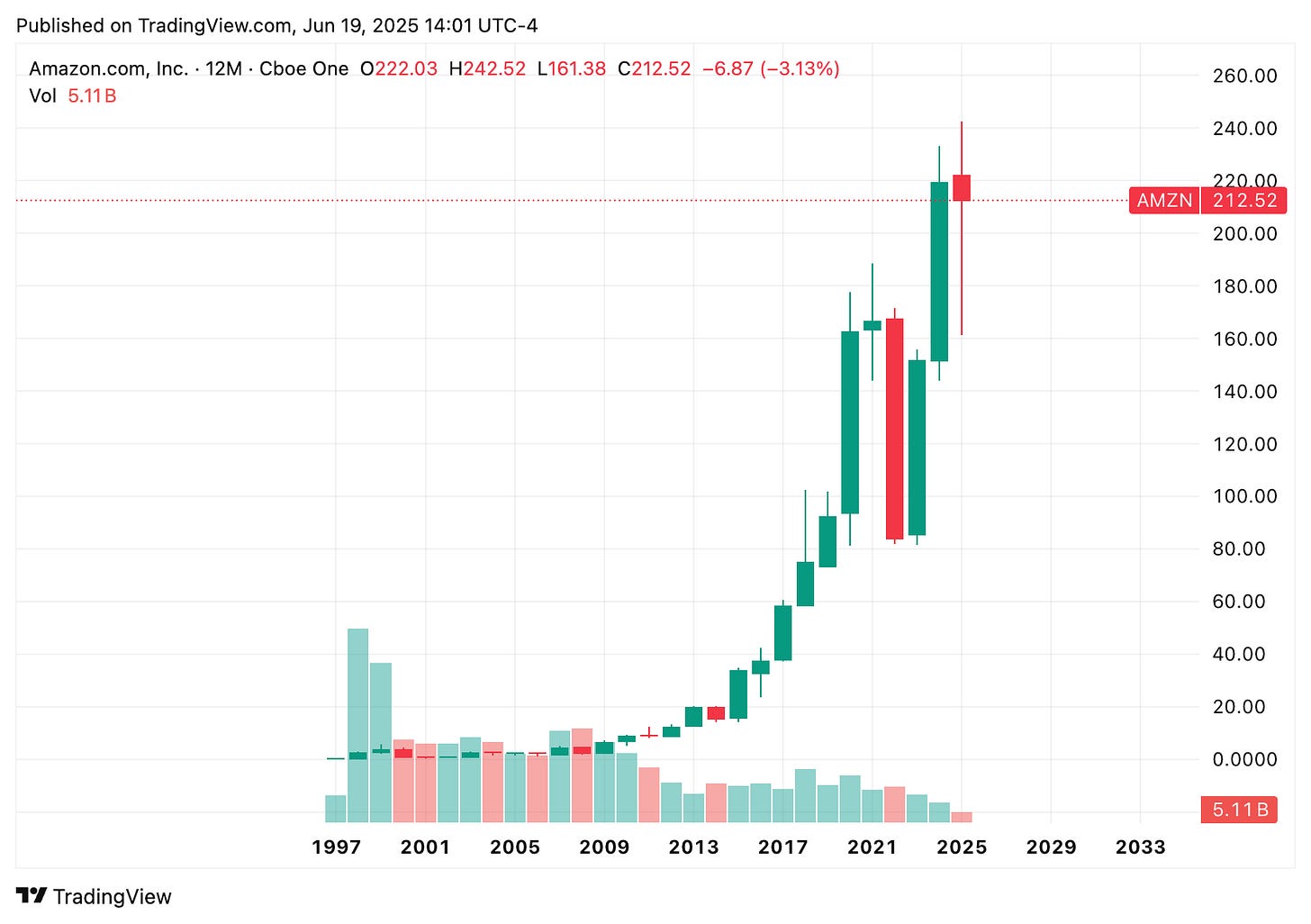

In an era when Amazon and other corporations are scouting the Southeast for server farm sites, this omission looms large. Will North and South Carolina end up footing the bill (in both dollars and emissions) to power distant cloud computing operations? The debate highlights a core tension in our energy future: do we double down on fossil fuels to chase growth at any cost, or do we invest in cleaner, community-scale solutions that can withstand a hotter climate?

An integral ecology perspective urges the latter, calling for energy plans that honor both people and planet. For instance, rooftop solar programs, efficiency upgrades, and resilient microgrids might not make headlines like a giant gas plant, but they could keep families safe during heat waves without extending our reliance on gas. As one utility executive in South Carolina admitted, reliability is essential – “when [customers] flip a switch or bump the thermostat, there’s going to be enough electricity” – yet how we achieve reliability is a societal choice. We can choose paths that empower local communities (creating jobs in solar installation, say) and cut carbon, or we can march along a familiar road where a few big companies call the shots. The heat is literally on to decide.

AI and Amazon: Technology’s Double-Edged Sword

Even as we confront environmental pressures, the Carolinas are also being transformed by technological forces – in particular, the rise of artificial intelligence and the reach of corporate giants like Amazon. These changes bring both promise and peril. On one hand, tech investment is pouring into our region. Not long ago, Amazon’s CEO Andy Jassy announced that the company will invest $10 billion in a new campus in North Carolina to expand its cloud computing and AI infrastructure. That project alone is slated to create at least 500 “high-paying” jobs in a rural county and support thousands of other jobs during construction. In fact, since 2024 Amazon has committed about $10 billion each to data center developments in states like Mississippi, Indiana, Ohio, and North Carolina, racing to meet exploding demand for AI services. Local officials often welcome these projects, seeing them as anchors of a new economy. And as a tech enthusiast for the majority of my life, I admit it’s exciting to think of Carolina farmland becoming home to cutting-edge AI research that could help solve problems in health, agriculture, and beyond. Maybe.

Yet there is another side to this story, one of displaced workers and disrupted communities. In early 2025, Jassy spoke with blunt honesty about what AI means for Amazon’s workforce. “We will need fewer people doing some of the jobs that are being done today,” he told employees, saying that as Amazon uses AI more widely, “we expect that this will reduce our total corporate workforce” in the next few years. In plain terms, many white-collar and technical roles could be eliminated by algorithms that optimize supply chains or generate code. Amazon has already cut tens of thousands of jobs since 2022, and more layoffs are likely on the horizon. This isn’t just an Amazon issue; across many industries, workers in the Carolinas are eyeing the rise of AI with anxiety. Will software replace accountants and paralegals? Will automated trucks displace freight drivers on I-85 and I-95? The fear of technological unemployment runs deep here, especially in communities that have already weathered manufacturing losses in past decades.

The 267th pope, a son of Chicago, is making the potential threat of AI to humanity a signature issue of his pontificate, challenging a tech sector that has spent years trying to cultivate the Vatican as an ally.

Over the past decade, many of Silicon Valley’s most powerful executives have flown to Rome to shape how the world’s largest Christian denomination thinks and speaks about their innovations. The leaders of Google, Microsoft, Cisco and other tech powerhouses have debated the philosophical and societal implications of increasingly intelligent machines with the Vatican, hoping to share the benefits of emerging technologies, win over the moral authority and potentially steer its influence over governments and policymakers.

From the Wall Street Journal, “Pope Leo Takes On AI as a Potential Threat to Humanity” 6/17/25

Amazon’s impact on labor goes beyond the specter of AI, extending into the very structure of regional economies. Over the past few years, Amazon has built a vast network of distribution warehouses across the South, including major fulfillment centers near Charlotte, Raleigh-Durham, Columbia, Greenville, and Charleston.

These facilities do bring jobs, but what kind of jobs and at what cost? Studies have found that when Amazon opens a new warehouse, the host county gains warehouse positions but “no new net jobs overall”, as Amazon’s gains often come at the expense of other local businesses. In many small towns, Amazon has become the only game in town for decent wages – a reality the company exploits. The company “tends to locate in areas with good transportation links that are also economically and socially deprived” and has no trouble recruiting in such places. As one analysis noted, Amazon often wields monopsony power (dominance as the sole buyer of labor); in these communities, “it’s either Amazon or nothing” for job seekers.

Inside those mammoth fulfillment centers, the work can be grueling and alienating. Employees speak of racing to meet robotic performance quotas, being electronically tracked every second, and even having vending machines dispense free painkillers to cope with injuries. The warehouse has been called the “new factory” of our era, with productivity pressures and health hazards similar to those of the factories of the past. And now, automation is creeping into those spaces too, with robots ferrying shelves to human pickers, algorithms timing every motion. Paradoxically, Amazon still needs human hands and eyes in these centers, but the pace is dictated by the machines.

It’s telling that labor organizing efforts have sprung up from the failed union vote at Bessemer, Alabama, to a nascent movement at a Garner, NC facility, signaling that many workers refuse to be treated as disposable parts. The struggle against Amazon’s model has even been framed as part of a broader fight “for racial and environmental justice, for health and safety, [and] for workplace democracy”, recognizing that how a company treats its workers is intertwined with how it treats communities and the planet.

An integral ecology outlook strongly reinforces this linkage: there can be no ecological well-being without social well-being. If an economy exploits people, it almost certainly exploits land and resources too, and vice versa. In practical terms, this means that questions of climate resilience in the Carolinas connect directly to questions of economic justice. Will automation and AI be deployed in ways that liberate workers (by reducing drudgery and creating new opportunities), or simply to discard workers and maximize profit? Will the benefits of high-tech growth (like those new data centers) be shared broadly, or will they mainly enrich distant shareholders while locals face higher electric bills and hollowed-out job markets?

The answers depend on who gets a say in shaping the future. At present, it can feel like global corporations and algorithms are setting the agenda, with ordinary Carolinians left to react. But alternative paths are possible. Indeed, this is where the wisdom of our visionary thinkers comes in, urging us to reclaim our agency.

Integral Visions: Wisdom from Berry, Teilhard, and Cobb

The challenges we face, climate upheaval, energy dilemmas, and technological disruption, are unprecedented in scale. But we are not the first to grapple with how humanity can live in harmony with nature and with its own inventions. Thinkers like Thomas Berry, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, and John Cobb devoted their lives to these questions, and their insights shine like beacons for the Carolinas today.

Thomas Berry, a Catholic monk and self-described “geologian” who spent formative years in Greensboro, NC, spoke often of the need for a new story to guide humanity. He saw that the old story of an Earth given to humans to dominate had led to ecological and spiritual ruin. Berry challenged us to envision the “Great Work” of our age: “to carry out the transition from a period of human devastation of the Earth to a period when humans would be present to the planet in a mutually beneficial manner.” This profound shift, he argued, is both a moral and practical imperative. I find Berry’s phrase “mutually beneficial” especially inspiring: it implies partnership with nature, a relationship where both humans and the more-than-human world thrive together.

What would it mean for the Carolinas to undertake this Great Work? It might mean restoring wetlands on our coasts to buffer storms while supporting fishing livelihoods, or redesigning cities like Charlotte and Columbia with green spaces that cool neighborhoods and uplift mental health. It certainly means viewing the universe not as a collection of objects, but as a communion of subjects, a favorite Berry aphorism. Every river, every forest, every community has inherent value and voice. Berry was actually one of the first to use the term “integral ecology.” For him, humans are not conquerors standing apart from ecology; we are integral to the Earth community. Thus, he wrote, “we need an ecological spirituality with an integral ecologist as spiritual guide.” In practice, this could be as simple (and profound) as learning from indigenous wisdom in our region, for instance, the Cherokee teaching that the Earth is our mother, or as global as Pope Francis’s call in Laudato Si’ for an integral ecology that links care of creation with justice for the poor. Berry gives us permission to be dreamers of a better world, but also reminds us that those dreams must be grounded in reverence for the soil under our feet.

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, a French Jesuit paleontologist, offers a vision that is cosmic and futuristic, yet deeply relevant to our high-tech concerns. Teilhard looked at evolution and saw it not as random chaos but as a purposeful journey of the universe toward greater complexity and consciousness. He coined the idea of the Noosphere as a layer of mind encircling the planet, born of human thought and culture.

Intriguingly, one could say the Internet, and by extension artificial intelligence, is a manifestation of the Noosphere. Far from viewing technology as something outside of nature, Teilhard saw it as a natural extension of our evolutionary process. In his eyes, technology is “a vital part of the human ecosystem” and an enabler of cosmic evolution, pushing us toward what he called the Omega Point, or a state of collective unity and enlightenment. This hopeful take stands in contrast to more pessimistic views of tech. It suggests that if guided by the right values, our inventions could help humanity converge in understanding and even love.

I imagine Teilhard would look at AI and ask: How can this tool elevate our shared consciousness? Perhaps AI could indeed free people from monotonous labor to engage in more creative, compassionate work, if we design economic systems to distribute those gains fairly. Teilhard was no naive optimist; he witnessed world wars and knew progress is not linear. But he maintained that “the future of evolution” is open-ended and that a higher, more harmonious global society is possible. For the Carolinas, Teilhard’s vision invites us to see our local efforts (be it a community garden or a tech startup incubator) as part of a much larger evolutionary story. It also invites us to embed ethics and spirituality into our technological endeavors.

An AI that maximizes advertising clicks is a low form of “consciousness,” but an AI used to, say, optimize regional water usage during droughts or to predict and mitigate flood impacts – that could be an ally in the Great Work. Teilhard’s blend of hope and caution resonates: he believed in the power of human innovation, “not as a force of destruction but a result of nature…with a purpose and direction.” At the same time, he would likely urge us to infuse that progress with amour, love, to “harness the energies of love” in his famous phrase, as the true guiding fire for humanity’s second act.

John B. Cobb Jr., a scholar of religion and ecology who just passed away last year and who also had strong ties to the Southeast, brings the discussion down to earth, to the level of communities and economies. Cobb emphasizes interdependence: every part of the ecosocial system affects every other. He has warned for decades that humanity’s most urgent task is “to preserve the world on which it lives and depends.” In the late 1980s, Cobb co-authored For the Common Good, which boldly critiqued the then-dominant global economic model. He argued that an economy fixated on endless growth and corporate profit was fundamentally at odds with ecological limits and community health. Instead, Cobb advocated “redirecting the economy toward community, the environment, and a sustainable future.” In effect, he foresaw the need to rein in corporate power and rebuild local capacity well before “localism” became a buzzword.

One of Cobb’s provocative ideas is what he and colleagues call an “ecological civilization,” a society where well-being, not GDP, is the measure of success; where cities produce their own energy and food sustainably; and where decision-making is decentralized and participatory. I’ve always been driven by his conviction that local economies must take precedence over global markets.

For the Carolinas, Cobb’s thinking could translate into a renaissance of community-based initiatives. Imagine energy co-ops in Appalachia harnessing wind power for local benefit, or cooperatives of farmers and consumers in the Piedmont creating resilient food networks. Cobb’s work affirms that top-down, one-size-fits-all solutions rarely work; sustainability grows from the bottom up, from empowered communities. This aligns perfectly with an integral ecology ethos, participation is key. People must see themselves not as passive subjects of change, but as protagonists shaping their destiny in concert with their neighbors and their land.

Participatory Futures: Carolina Communities Take the Lead

As I reflect on all this, I realize integral ecology is not a distant ideal, but it’s already emerging in bits and pieces across the Carolinas. Our task is to connect these pieces into a coherent movement. This means building unlikely alliances: climate activists with labor organizers (because a just transition means good green jobs), churches with scientists (because moral imagination and empirical knowledge together can move mountains), rural farmers with urban planners (because their futures are intimately linked), and so on. In my mind’s eye, I often picture a Carolina Future Council of sorts, a gathering where all stakeholders, including the rivers and forests, spoken for by environmental stewards, have a seat at the table. What if state and local governments formally adopted an integral approach, assessing policies by their impact on all dimensions of well-being? What if youth were invited into every planning meeting to represent the voice of future generations? These are not utopian fantasies; they are practical steps toward what Thomas Berry might call the Ecozoic Era, a time when humans live in a mutually enhancing relationship with Earth.

Choosing the Carolina We Want

Standing at this crossroads, the people of North and South Carolina face a fundamental choice. We can continue on the path of least resistance, letting climate disruptions accelerate, allowing corporations and AI technologies to dictate how we live and work, and defaulting to top-down solutions that may keep us comfortable today but impoverished tomorrow. Or, we can choose another path: one of conscious, collaborative action to shape the kind of future we actually desire. The wisdom of integral ecology tells us that this choice cannot be made in isolated arenas; it must be integrated. The Carolinas’ climate resilience, economic justice, technological innovation, and cultural spirit are all interconnected strands of one tapestry.

As John Cobb reminds us, the task of preserving our world is urgent and falls to all of us. And as I have seen, when Carolinians come together – whether to restore a marsh, guide an energy project, or advocate for fairness at work – we tap into something powerful. We tap into our shared love for this land of sandy shores and pine forests, rolling hills and mill towns, bright city skylines and quiet farms. We also tap into a deep well of hope. Not a naive hope that someone else will fix things, but a grounded hope born of participation and trust. In those moments, I sense the Carolinas writing a new story for themselves.

In that story, integral ecology is not a concept in a book; it is a living practice. It means a coastal Carolina family can weather a hurricane because their community invested in natural buffers and microgrids after listening to scientists and elders. It means a South Carolina line worker can come home safe and proud because his utility prioritized a just transition to clean energy, instead of squeezing workers to boost profits. It means an Amazon warehouse employee in the Piedmont has a voice on the job and maybe a shorter workweek, because AI took over the mindless tasks, and the productivity gains were shared. It means our children learn in school not just about the Civil War and the Space Age, but about the Noosphere and the Great Work of our time, and they grow up feeling excited to be part of it.

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin wrote, “The future belongs to those who give the next generation reason to hope.” Today, I see many reasons to hope in the Carolinas. Our crises, climate, economic, and technological, are real, but so are our capacities to respond with intelligence and heart. We are descendants of people who endured and reinvented themselves through wars, Reconstruction, the civil rights struggle, and economic upheavals. We have in our cultural DNA the resourcefulness to adapt and the faith to begin anew. By embracing an integral ecology mindset, we can ensure that the changes sweeping our region do not wash away what we cherish, but rather carry us to a brighter shore.

The kind of future we want is one where the Carolinas are thriving, ecologically flourishing, socially just, economically inclusive, and spiritually fulfilling. No one will hand us this future ready-made. It will be crafted, decision by decision, action by action, by us, the people of this beautiful corner of Earth. The invitation is open to everyone to take part. As for me, I’m determined to remain a participant in this unfolding story, not a bystander. With grounded sincerity, I believe that if we continue to learn from wisdom figures, listen to each other, and stay rooted in our local realities, we will not default to any “apocalypse.” Instead, we will consciously choose life, and in doing so, become a beacon for others. The Carolinas can lead the way in showing what an integral ecology looks like on the ground: hopeful, participatory, and ever-aware that everything is connected.

In the end, the future of the Carolinas will be the future we co-create as Pope Leo is indicating. Let’s make it one that our grandchildren will thank us for, with sunlight in their homes, meaningful work in their hands, and the wild geese still calling overhead on an autumn dawn. Such a future is within our grasp, if we have the courage to imagine it – and the conviction to make it real.

“The future belongs to those who give the next generation reason to hope.”

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin

Relevant Links:

Ray Levy Uyeda, Prism, “In North Carolina, Trump administration’s anti-climate deregulation agenda comes to a head,” March 13, 2025 (archived) – on NC fossil fuel infrastructure and climate vulnerability.

Jeffrey Collins, Associated Press, “Under a hot summer sun, South Carolina’s governor says energy law will keep air conditioners humming,” June 18, 2025.

AP News, “Amazon CEO says AI will reduce its corporate workforce in next few years,” June 2025.

Sean Kelly, “Five Principles of Integral Ecology” – on the scope of integral ecology.

Thomas Berry, The Great Work – on transitioning to a mutually beneficial presence on Earth.

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, discussed in Elias Kruger, “Teilhard’s Hope: Technology as an Enabler of Cosmic Evolution” – on seeing technology as part of evolution.

John B. Cobb Jr., interview in Ecozoic Journal – on humanity’s urgent task to preserve the world and the need for local economies.

Duke Energy’s Stock Performance:

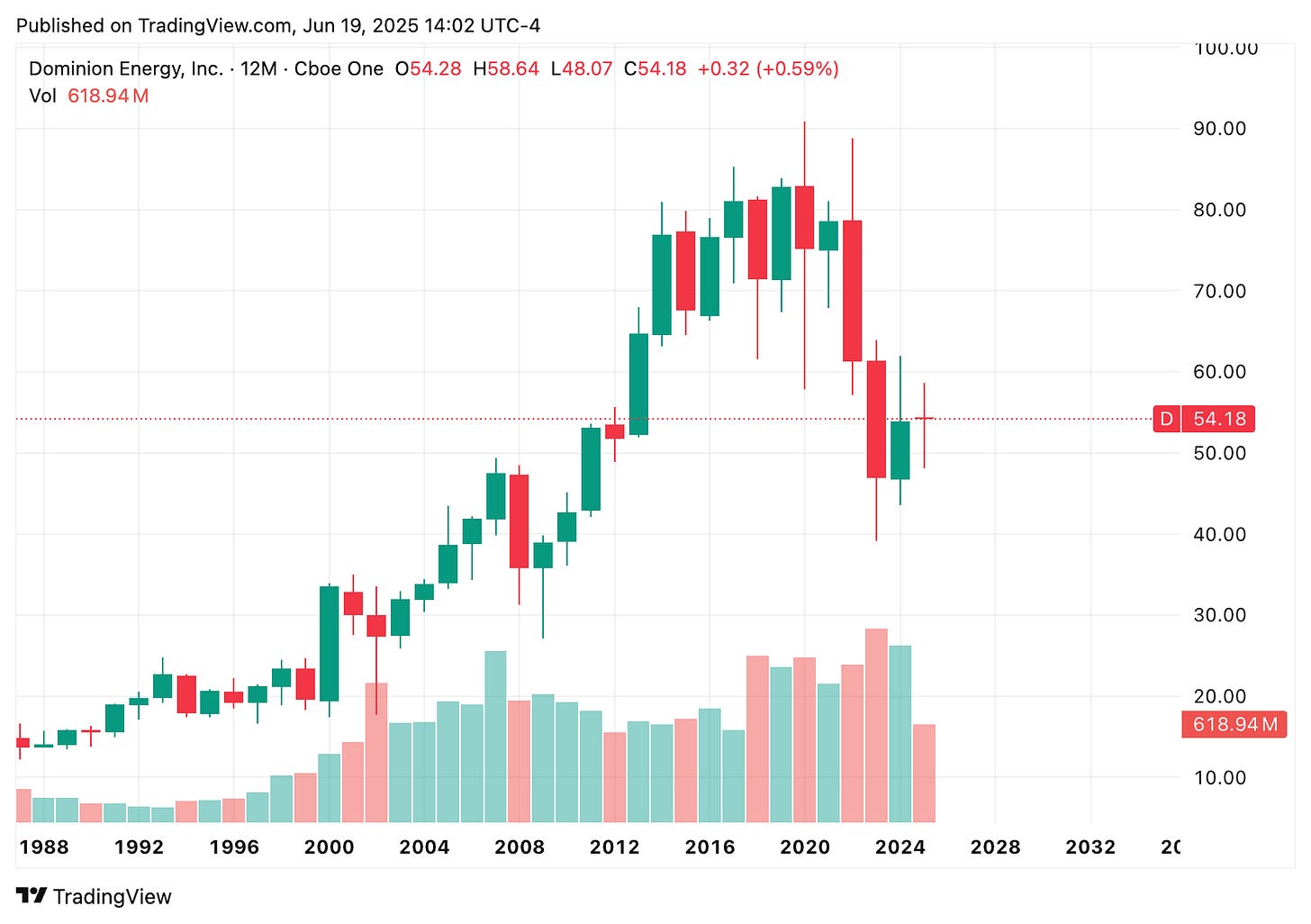

Dominion Energy’s Stock Performance:

Amazon’s Stock Performance:

Great article. Some more thoughts on where Teilhard and technology can intersect in a future complexity consciousness: https://open.substack.com/pub/fairytalesfromecotopia/p/the-spirit-of-artificial-intelligence?r=2frou4&utm_medium=ios&utm_campaign=post