Carolina Ecological Intentionality

How Slowing Down Our Attention Changes How We Relate to the Wider World

In a world dominated by speed (fast news cycles, quick fixes, social media video scrolling, and shorter attention spans), our capacity to attend deeply to the places we live, love, and lose is a radical act of ecological care. Philosophers of perception remind us that attention isn’t merely about what we notice, but it’s about what we allow to shape us. When we intentionally orient our attention toward the ecologies around us, we begin to see not only the obvious trees, rivers, and species but also the processes, histories, and relationships that sustain them. I call this ecological intentionality, or the practice of attentive presence that recognizes humans as part of, not apart from, the living world.

In the Carolinas right now, several stories show why this kind of intentional attention matters not as a luxury, but as an ecological necessity.

Coastal Wetlands: Hidden Engines Under Our Feet

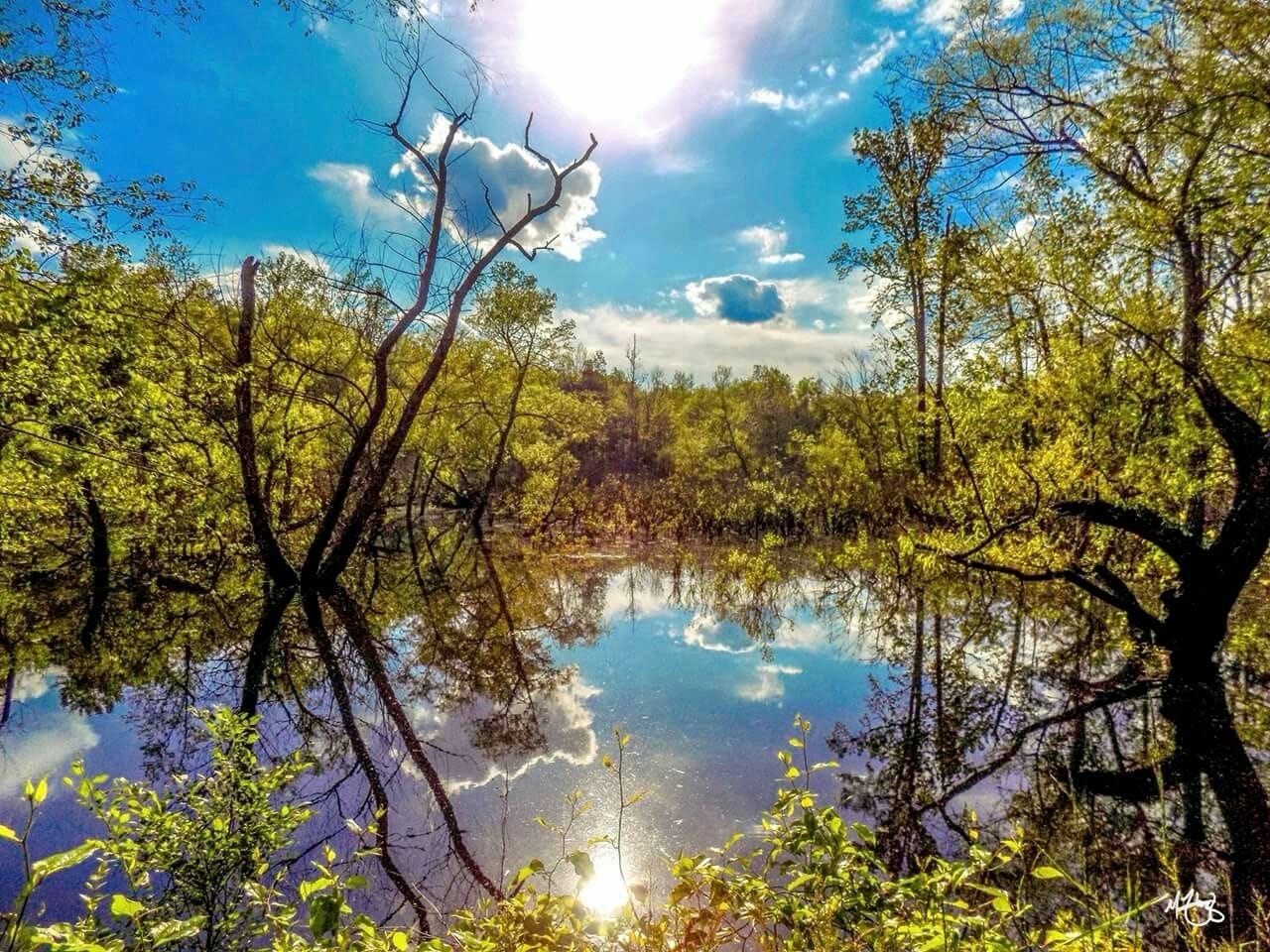

On the Carolina coast, salt marshes and submerged seagrass beds are quietly doing the hard work of climate regulation. These coastal habitats are not just scenic landscapes; they are carbon storage powerhouses, capable of locking away vast amounts of carbon and even exporting “good carbon” that alters the chemistry of surrounding waters, which is something scientists are only recently beginning to understand.

To attend to these places with ecological intentionality means seeing beyond their surface beauty. It means noticing the rhythmic tides that shuttle nutrients back and forth, and perceiving how human choices (from development to conservation) deeply alter these processes. When we look closely, we see that protecting wetlands isn’t just aesthetic or recreational, it’s materially tied to how resilient our coastal communities will be in the face of sea-level rise and storm surge. I often notice how many “do not consume fish/shellfish from these waters!” signs appear when our family visits the Carolina coast and we visit a salt marsh. That’s the direct consequences of human action and inaction, and later human generations have to pay the opportunity cost of industry. It doesn’t have to be this way.

Forests and Urban Trees: What We Lose When We Don’t Look Closely

In Chapel Hill, an accelerating loss of urban tree canopy reveals a slow process only perceptible when we pause to observe over years and decades. Once-cool, shady streets are now brighter and hotter because buildings and pavement are replacing living trees.

When we practice ecological intentionality in these cases, we don’t just see trees as ornaments in a landscape, but as active participants in the city’s climate, air quality, and community well-being. Paying attention to where shade has disappeared reveals inequities, too, with neighborhoods that lose trees often overlapping with those facing heat stress and economic vulnerability. That’s especially true here in South Carolina metropolitan areas, as well, from the Upstate to the Lowcountry.

Rivers and Storm Aftermath: The Importance of How We Clean Up

Natural disasters like Hurricane Helene leave visible devastation, but some of the most consequential damage is subtle, such as the disturbance of riverbeds and sensitive habitats by cleanup crews working to restore human transportation, electrical, and technological infrastructure. Even though these are sometimes required in the immediate aftermath, we should note them for the future as we prepare for future disasters of scale that will affect the Carolinas in an era of climate change. Investing in the future takes attention and careful planning to ensure that we’re doing all that we can now to enable future human generations to live sustainably with our ecosystems and ecologies.

Here, ecological intentionality asks us to think not just about restoring what was lost in a human sense, but about how processes of restoration can either repair or further harm ecological systems. What if our first impulse wasn’t just to remove debris as quickly as possible, but to listen to river flow, sediment movement, and the needs of aquatic life before mobilizing heavy machinery?

Wildfire, Fire Management, and the Rhythm of Change

Across the Carolinas, changing fire patterns, from wildfires to prescribed burns, reflect an ecosystem in transformation. In Western North Carolina’s mountains, landowners are increasingly using prescribed burns to reduce fuel loads and restore ancient fire regimes. This ancient practice (both human and more-than-human) directly shapes the soil, plants, trees, animals, and microbiomes, and holds the potential to help us reckon with a changing planetary climate as our ancestors did.

Ecological intentionality here isn’t just about controlled ignition. Rather, this practice is about understanding fire as a participant in ecological cycles, not merely as a destructive force. It invites us to see fire’s role in nutrient cycling, species composition, and landscape resilience. Such a perspective requires deep listening to the land itself, to those Indigenous communities who have managed these ecosystems for generations, and to emerging climate realities.

Toward a Practice of Careful Attention

These diverse stories from the Carolinas, from wetlands to urban trees, river cleanup to fire management, all have something in common. They reward intentional attention. When we simply skim environmental headlines, we miss the rhythms and feedback loops that define ecological health. But when we slow down, when we notice patterns over time and across ecosystems, we start to understand that human lives and ecological processes are entangled in ways that demand our participation, not just our observation. We are integral to our local ecologies just as our local ecologies are integral to each of us.

Ways to Practice Ecological Intentionality

Read with depth, not breadth. Instead of scanning headlines, take time to follow one local ecological story across weeks or months. Notice how policy, science, weather, and community responses interact.

Engage with place physically and perceptually. Spend time in a local wetland, park, forest, river, or neighborhood street tree canopy. Practice noticing seasonal shifts, species interactions, soil moisture, and human impacts.

Correlate personal attention with collective action. Local environmental policy often reflects what people care enough to talk about from those who have the privilege of time to be heard. When attention deepens, advocacy becomes grounded not in slogans or political rhetoric, but in lived ecological knowledge.

Intentional thinking, or what I call ecological intentionality here, is not an abstract philosophy. It’s a skill, a practice, and an invitation to perceive beyond the superficial. In our news from the Carolinas today, we find countless invitations to slow down, pay attention, and participate more thoughtfully in the ever-unfolding story of our shared ecologies.